Part 1: Why does museum documentation practice need to be decolonised?

This post is an edited version of the presentation I gave at the Decolonising the Database webinar hosted on Monday 5th July by the Centre for Design History, University of Brighton. I was honoured to share a virtual stage with Anjalie Dalal-Clayton, Ananda Rutherford, Hannah Turner, Shelley Angelie Saggar and Kelly Foster. I used the opportunity to share an update on my Developing Your Creative Practice project, funded by Arts Council England.

My DYCP work did not focus exclusively on decolonisation, rather I saw colonial legacies as one of many problems inherent to our approach to collections. I will always advocate for the importance of ‘basic’ documentation work (what museums have and where) and the need to get our houses in order. But I question whether, if we were to carry on with the same systems of documentation we have been using, we would be perpetuating harm.

We are working with the legacies of systems of knowledge that were created by a privileged few to make sense of the world, but also to justify and solidify a hierarchical system which placed them at the top as the holders of knowledge and power.

My intention in the project was to focus on three areas:

- How our systems have developed?

- How new digital technologies could change these systems?

- And how people are engaging with collections online?

This first post summarises my thoughts on question 1, with an extremely brief history of collections documentation. Part 2 will explore my thinking about how new digital technologies could change these systems (spoiler alert: it’s not the technologies that are the problem). However, despite the push to increase digital content and engagement that happened as a result of the 2020 lockdowns, there is precious little publicly available research being done to address point 3, so that remains a work in progress.

How our systems have developed

In keeping with the database theme of the webinar I made some jazzy slides using a template designed for a tech company, so it seemed apt to keep in the ‘about the team’ segment reflecting on the museum tech bros of the past.

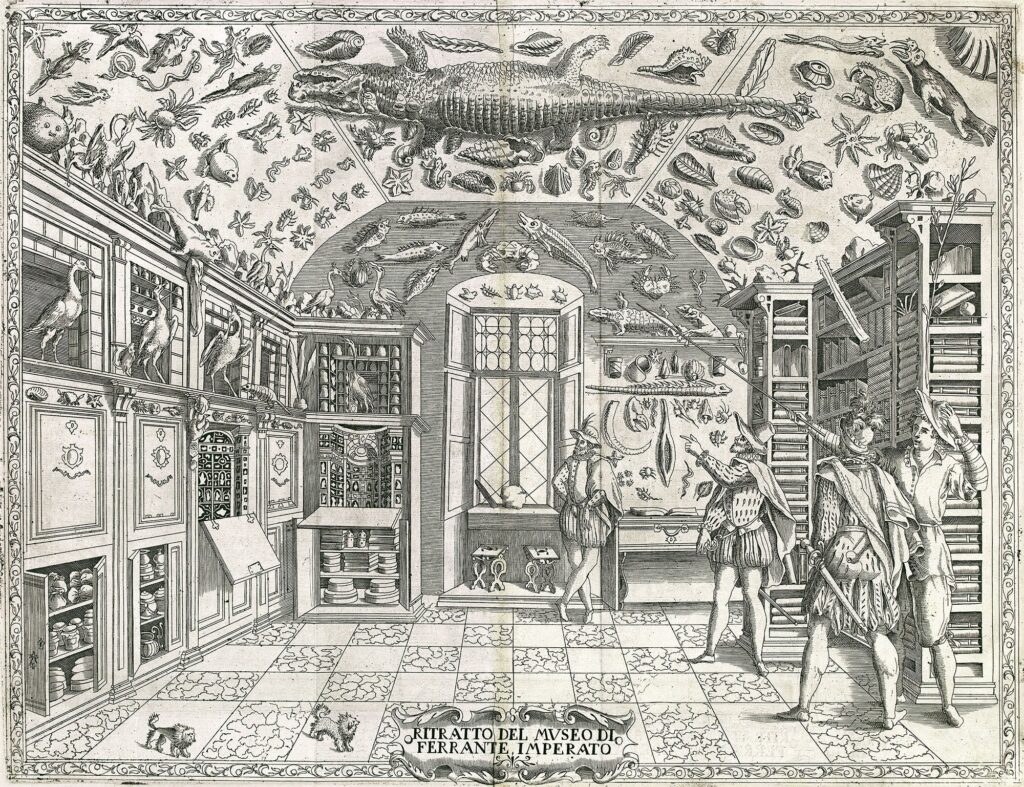

It has become accepted that museums were created as the store houses of colonial loot, and that is a significant phase in UK museum history, but it’s worth remembering that museums in their earliest incarnation predated the height of European empires. The so-called cabinets of curiosity were displays of power, but it was of individual power through the accumulation of wealth and access to unusual and exotic things.

We tend to think of the earliest museums, cabinets of curiosities, as chaotic and disorderly. In fact, they did have an order.

Ordering early collections

Because I am interested in the people doing the work, my reading about early museums led me to Samuel Quiccheberg (1529-1567). He was not a collector himself, but was employed by wealthier men to manage their collections. In 1565 he published his Inscriptiones, also called ‘The First Treatise on Museums’ a guide to arranging the contents of a cabinet.

Quiccheberg’s system for organising princely collections divided the contents into 5 classes.

There are a few things to say about this: the first category is concerned with the founder of the collection. This is a great example of how museums have always reflected the people who have made museums, just as much if not more than they do the subjects on display. The second thing to note is that there is no hierarchy of artefacts that come from the local region, and those that come from far way. Nor is there a hierarchy applied to older artefacts and more contemporary ones. This was not part of the agenda at the time.

The collections in cabinets were still fairly small. There is a theory that we are all able to easily classify the animals, plants and things we encounter in our natural environment, or ‘umwelt’ without too much trouble, but when there is more material, we need to employ categories and systems. In museums we are dealing with an unnatural amount of material.

Hierarchical classification

In the period of global exploration, naturalists and collectors were encountering vast numbers of new species and wanted to name and claim them all. Carl Linnaeus formalised binomial nomenclature, giving scientists a standardised naming format, and set out a hierarchical, rank based classification of organisms.

Race science

Some early UK museums, such as the Ashmolean and the British Museum, are the product of this period of exploration. As places where the new natural sciences were enacted, the museum’s task became managing the material evidence of a few men’s attempts to order and claim the world. As Angela Saini details in her book Superior: The Return of Race Science, this period was also when classification of nature and things turned to people.

“It was not long after the British Museum was founded that European scientists began to define what we now think of as race. In 1795, in the third edition of On the Natural Varieties of Mankind, German doctor Johann Friedrich Blumenbach described five human types: Caucasians, Mongolians, Ethiopians, Americans and Malays, elevating Caucasians – his own race – to the status of most beautiful of them all.”

Saini, Angela. Superior: The Return of Race Science . HarperCollins Publishers. Kindle Edition.

Evolution

Charles Darwin, with the On the Origins of the Species, pioneered ideas about evolution. This was a problem for taxonomists who were tied to the idea of discrete, unchanging categories, but of course the theory was eventually accepted.

The evolution of culture

To bring the narrative back to museums, Pitt Rivers took the idea of the evolution of species and applied it to cultures.

“The classification of natural history specimens has long been a recognized necessity in the arrangement of every museum which professes to impart useful information, but ethnological specimens have not generally been thought capable of anything more than a geographical arrangement.”

Pitt Rivers, The Evolution of Culture

In other words he thought, I can take the arrangement of objects, and make it racist.

Pitt Rivers and those like him believed not only in evolution but in the degradation of cultures – that a group of people could go backwards.

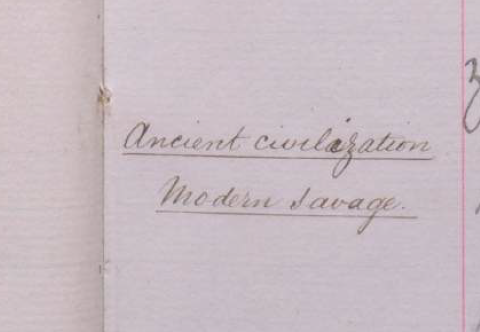

In documentation, this manifested in a separation between archaeological finds attributed to some ‘ancient civilisation’ and contemporary objects sources from ‘modern savages.’ These ideas also influenced what museums have considered to be an ‘authentic’ object. Objects showing cross-cultural influence did not fit neatly into the narrative Pitt Rivers was trying to tell.

How does this filter down to the history of your museum?

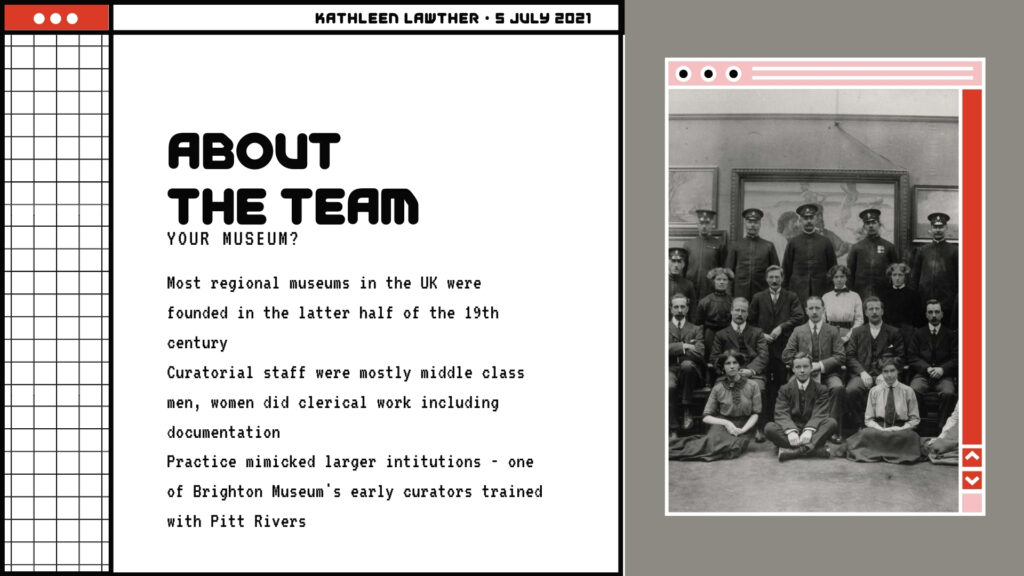

Most regional museums in the UK were founded in the latter half of the 19th century, and practice mimicked larger institutions. Curatorial staff were mostly middle class men, with women doing education and clerical work including documentation.

The above image shows some members of the team at Brighton Museum in the early 20th century. The man on the far left of the second row is Herbert Samuel Toms, who trained directly with Pitt Rivers. The image of the handwritten ‘ancient civilisation / modern savage’ note above is actually from Brighton Museum’s historic accession register, showing Pitt Rivers’ influence.

The evolution of my thinking

When I started my project I was interested in alternative ‘ways of knowing’ – different ideas about how to name and describe things, and how to incorporate knowledge systems of the cultures from which objects originated into the museum.

However, when thinking about the unique problem that museums have as the storehouses of the past (including their own pasts as instruments of colonial power) I realised that some degree of categorisation is always going to be necessary in order to deal with the vast amounts of collections we hold.

Further more, attempts to incorporate indigenous ways of knowing into western museum systems could be seen as an extension of extractive colonial practice, rather than an undoing of it. Instead of looking to source communities for answers to a problem of our own making, we should fix our own systems.

Part 2 will address some calls to action…