This week I visited Myth Quest: Monsters and Mortals, an interactive exhibition at the Great North Museum: Hancock, as part of a tour. I did not have the opportunity to view the whole exhibition, which forms a gamified trail throughout the museum, so I am not attempting to write a review of the exhibition or experience, but rather to focus on one particular area of the display. I found the display of world cultures collections within the exhibition incredibly problematic, and I want to explain why, because I think its relevant for other museums which are engaging with decolonial practice.

The museum has a series of policies on their site around Sensitive collections, repatriation and decolonisation. This includes a published list of all the objects in the museum’s world cultures collections, along with some information about their provenance, which is admirable and shows a level of transparency not matched by most museums with similar collections and histories. However, in order for museums to engage with decolonisation in all areas of practice, it is important to understand the history of colonial display and what it is we are trying to undo and move away from when we ‘decolonise’ museums.

I have shared much of this feedback with the museum team, but I wanted to write about this more openly because looking at positive reactions online to the Myth Quest interactive overall, I was left thinking ‘Is it just me?, Is no one else seeing what I’m seeing?!’

So this is what I saw.

Myth Quest begins with a fictionalised version of Mary Hancock, sister of the museum’s founders, explaining to visitors that they are about to see objects she has collected in a parallel world, called the Parallel. The gallery is styled as an old-fashioned office / archive, with objects in display cases, as well as wooden crates positioned around the gallery to set the scene.

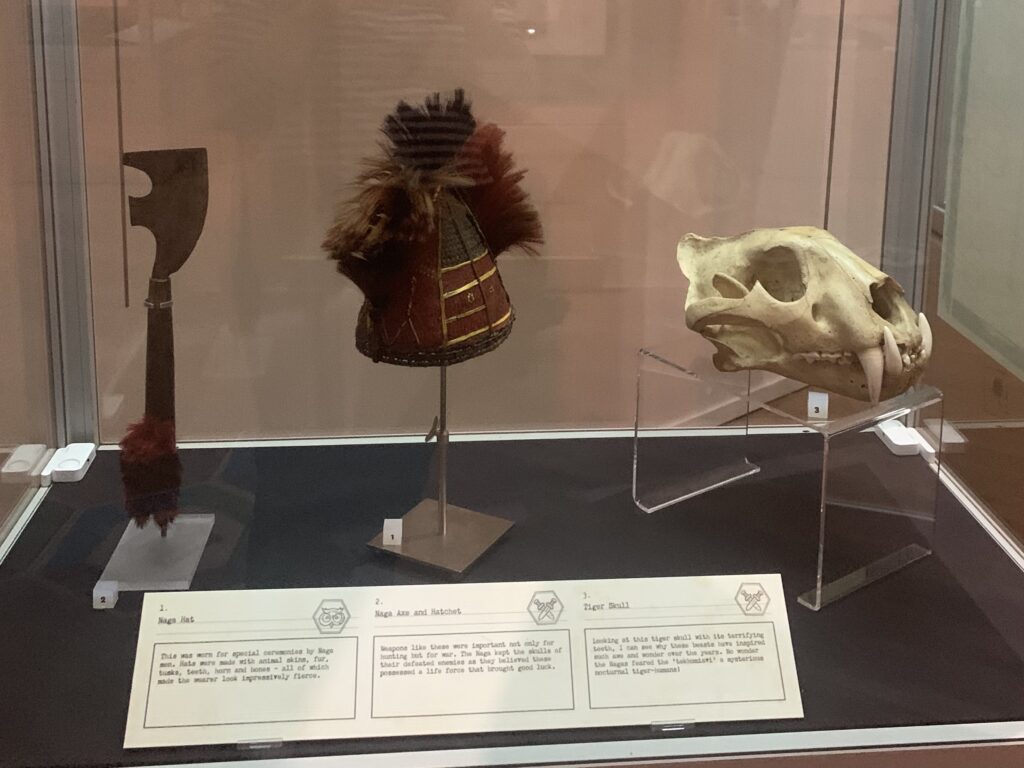

The choice to present world cultures collections as part of ‘The Archive’ section of Myth Quest and to uncritically employ historic labelling and interpretation meant that the use of these objects in the exhibition replicates a series of colonial museum tropes.

Focus on weaponry and objects associated with violence.

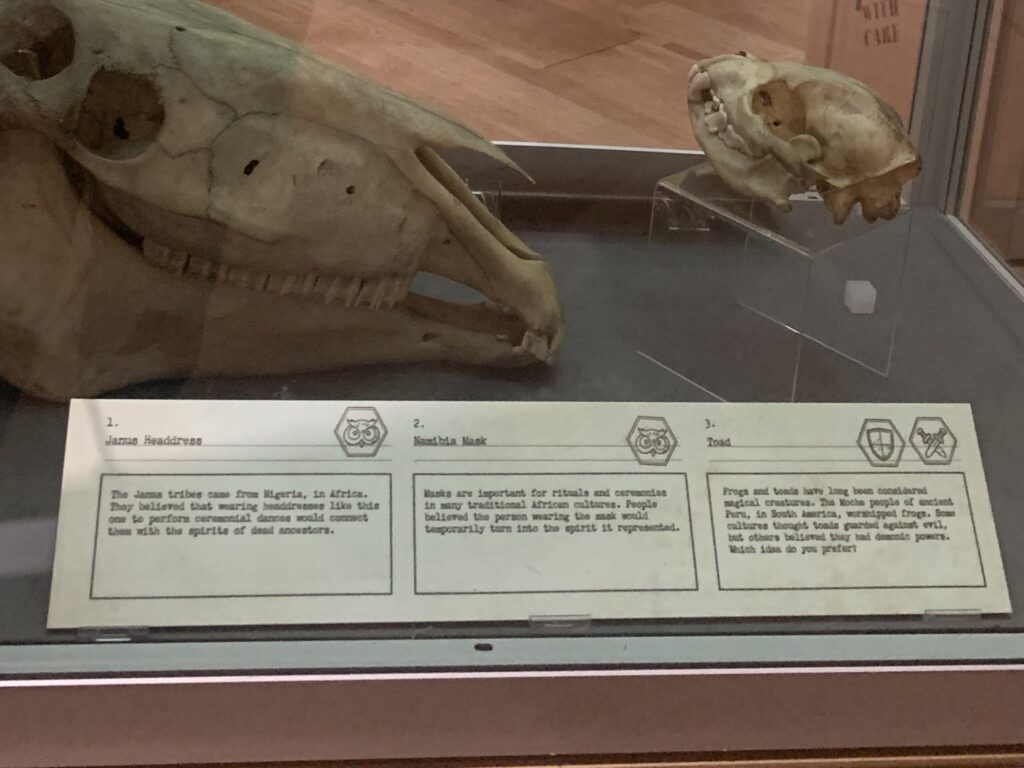

From what I saw, all the African objects were in the attack/defence/wisdom section, along with Naga objects and a club ‘from New Zealand’.* This is problematic because it is repeating the trope of historic museum displays that portrayed colonised peoples as inherently violent and therefore needing to be ‘civilised’ by colonial powers. This is enforced in the exhibition with the use of words like ‘savage’ and ‘fierce’.

Writing about Indigenous peoples in the past tense, rather than as living cultures.

See, for example, advice from the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian :

‘Only using the past tense reinforces the myth of the “Vanishing Indian” and negates the experiences and the dynamic cultures of Native peoples today… Use the present tense and make Native Americans relevant and contemporary.

Emphasize that Indigenous peoples have living cultures that change over time. If you do need to use the past tense, provide context by including dates. Otherwise, it may seem like Native cultures are no longer living.’

World cultures collections presented alongside natural history collections

In the display of Naga items this is coupled with the label ‘Hats were made with animal skins, fur, tusks, teeth, horns and bones – all of which made the wearer look impressively fierce.’ Again this felt uncomfortably close to historic displays that portray some cultures as other and inferior, aligning them with the animal rather than human world.

Presenting indigenous beliefs as mythical/supernatural/fantasy.

In the short time I had in the exhibition, it was really unclear to me the extent to which the written labels were supposed to be part of the fictionalised narrative. Including cultural objects in this fictionalised world presents the objects and beliefs associated with them as fantastical and imaginary, rather than respecting the cultural beliefs of source communities.

In the opening letter device attributed to Mary Hancock it states that what audiences are about to see has since been ‘Dismissed and dismantled by science’, which again, with its blurring of the narrative and the physical presentation of the objects, can be read as saying that the cultural beliefs associate with the objects have been dismissed and dismantled by [superior, western] science.

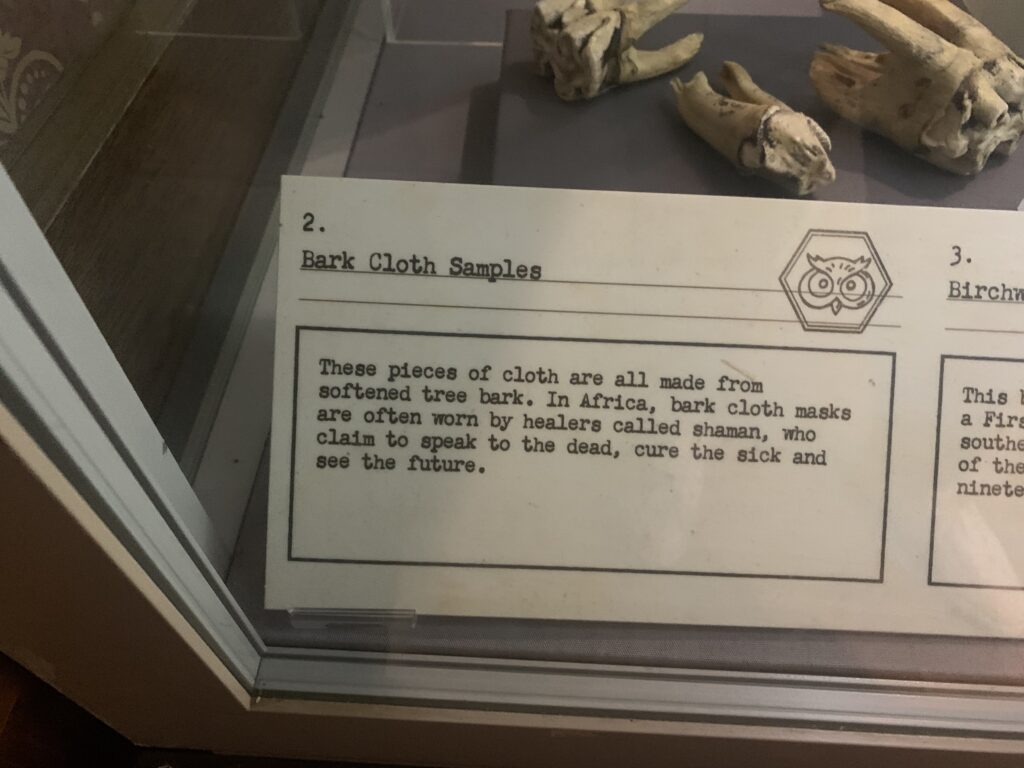

Writing about Africa as if it is a country, and as if Africa has one homogenous culture.

For example: ‘In Africa, bark cloth masks are often worn by healers called shaman who claim to speak to the dead, cure the sick and see the future.’

I also noticed vague references to peoples and geographical areas, such as ‘the Basongye people of West Africa’. I did a quick internet search and found that Songye people are from the DRC, ie central Africa. If you are able to name a specific people and location, this is always preferable to being vague.

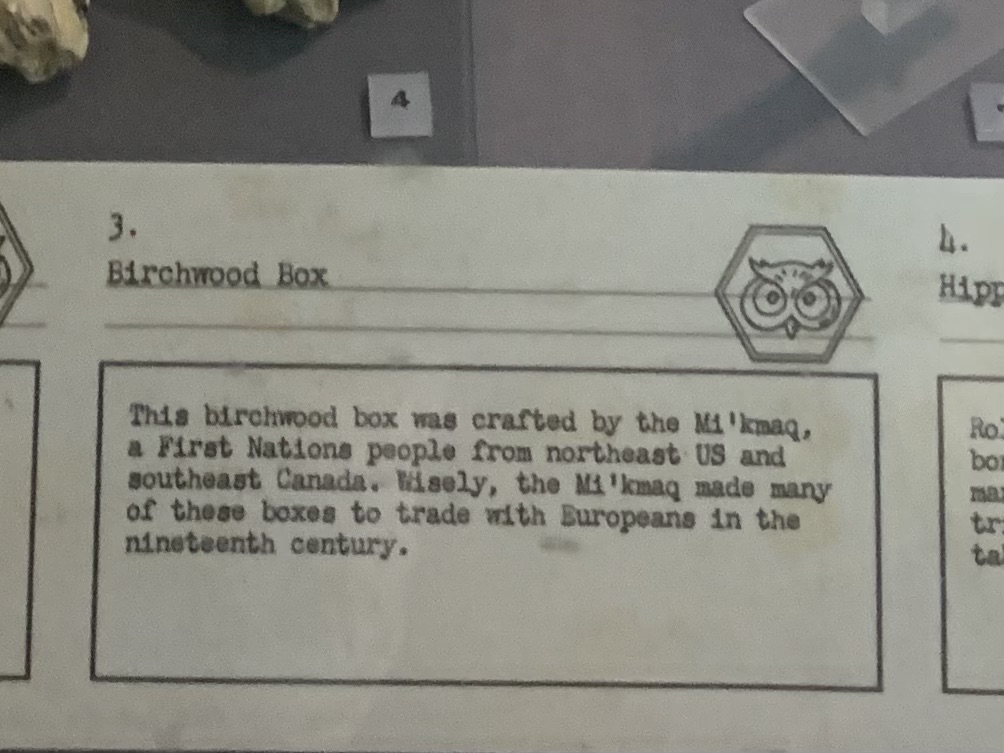

Centring contact with Europeans

This is evident both in the information labels about some individual objects, eg ’Wisely, the Mi’kmaq made many of these boxes to trade with Europeans in the nineteenth century’ as well as within the wider narrative concept of the display, where these cultural objects are simply used as props to tell a fantastical story which centres the character of Mary Hancock.

Before seeing this display, I would have thought that most people would be aware of these tropes and actively avoid them in planning new interpretation. The MA’s decolonisation guidance section on labelling provides useful tips on some of these issues:

‘The following questions are a starting point to help reappraise or create a text:

- Does the text treat the coloniser version of history as the only perspective?

- Does the text recognise the humanity of individuals, groups and communities?

- Has the text been informed by biases and stereotypes? Does the text use any offensive terms?

- What other sources of information or narratives could help to provide more context? Who could you work with to develop the text?

- Are you using clear explanations? Can you avoid using jargon and academic language? Use plain English and clearly explain what you mean and why it matters.

- Does the text acknowledge how an item or collection was acquired by the museum?’

Beyond the text used, museums should be acting with the utmost care about how they present and use world cultures collections. Because I wanted to focus on the repetition of colonial display tropes, I haven’t mentioned the obvious point that these are colonial collections completely divorced from not only their cultural meaning, but from the colonial context in which they entered the museum.

*While transcribing this label (all labels are transcribed in the alt text) I thought I should check the term Totokia, as I am not familiar with it. According to wikipedia, totokia originate from Fiji. Again I find it hard to tell whether this is part of the fictionalisation of the labelling around the collections or just bad information.