If the Culture Secretary wants to put a content warning on the The Crown, go for it, but put one on the door of every museum while you’re at it.

Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden, who earlier this year wrote to museums about the government’s position on problematic statues, is cracking out the headed paper again. This time it is reported that he is writing to Netflix to suggest that The Crown needs a content warning to remind viewers that it is a work of fiction. In its breathless report, the Mail on Sunday, which has itself ‘led calls for a disclaimer’ to be added to episodes of the show, quotes a friend of Prince Charles calling The Crown ‘highly sophisticated propaganda.’

To recap, that’s Statues: fact, good, history; TV shows: fiction, bad, propaganda

Let’s wind this back a bit. In 2020 problematic statues of slave traders/colonialists/confederates have been toppled/dashed into the sea/quietly removed/defended/debated. In this ‘debate’ there is one thing many commentators seem to agree on: what should happen to the statues if they are to be removed. They should be put in a museum. So people can learn from them. Learning about the past is good. But only if you learn it from a government approved source.

Of The Crown, Dowden says ‘Without this [content warning], I fear a generation of viewers who did not live through these events may mistake fiction for fact.’ This acknowledges that watching the show is a way many younger people have become interested in British history. I have had conversations with millennial friends who had never heard of, for example, the Aberfan disaster until they saw it on The Crown. What Dowden’s perspective is missing is that he does not trust viewers to take what they watch with a pinch of salt. People can watch the show, phone in hand if they want to, fact-checking as they go. They may first hear of an event on the show but if their interest is piqued they will generally do a bit of further reading. Isn’t that what champions of history want? For people to be interested in something and be inspired to find out more for themselves?

People want to watch The Crown. It’s entertaining and it might spark an interest in history. But it doesn’t have a social responsibility to spark interest in history or to present an approved, impartial story, which Dowden believes museums do. To return to the statues, do people want to look at ugly old racist statues in a museum? Or is that just the only thing people can think of to do with them? What is the museums’ responsibility to present an ‘impartial’ story?

Back in the summer, my reaction on seeing a clip of the Colston statue being winched out of Bristol harbour into which he had been so joyously thrown was one of disappointment. In a period of unrelenting bad news, I enjoyed watching the crowd in Bristol cheer as he went in. It was cathartic, even for me, a couple of hundred miles away, still stuck at home watching on Twitter. Reading that the statue would now become part of Bristol’s museum collections I initially groaned. Subsequent details about how they would preserve the paint protestors had thrown on the statue, and the ropes used to pull it down, reassured me that the museum would do its best to contextualise the statue in the moment of its downfall, not its previous life on a pedestal. From my few visits I have seen that Bristol museums already do a decent job of addressing the city’s links to slavery, although all museums can and should do more to address problematic histories.

How do other museums deal with problematic statues? Two quite different approaches are taken at the ultimate problematic museum, the Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium. I visited in February 2020 (over the course of four days my group only had one brief conversation about the virus. It was a different time). At the time I didn’t feel able to tweet or blog about it. I shared some thoughts when Belgium came up in the #museumsunlocked campaign. Now the subject of Bad Statues is more pertinent than ever, I wanted to revisit those thoughts here. (I’ve unrolled my Twitter thread at the bottom of the post).

There are two distinct approaches to problematic statues at the RMCA. The first is the ‘storage’ display detailed in my tweets. Statues are presented off to the side of the first gallery of the museum, with some text describing how problematic they are. They have been literally and conceptually de-centred. The second approach is for the statues which are part of the fabric of the building, including a gold statue of Leopold II which presents him as a saviour to the Congolese figures depicted with him. This, unnamed ‘friend of Prince Charles’, is what propaganda looks like. We were told that the museum could not move these statues because they have the Belgian equivalent of listed status. Statues: good, remember.

Despite their efforts to de-centre the monuments to Leopold, including artistic interventions in the rotunda where the statues are positioned, and reorientated the entire building so you come in a different entrance, he is still there. He’s gold. The museum was built as propaganda for him and his colonial project and now bureaucracy prevents this gold effigy of him being taken down from its pedestal.

This brings things back to the Culture Secretary and his letter to arms-length bodies funded by DCMS on HM Government’s position on contest heritage. (Incredibly this link from gov.uk allows you to download a word document, not a pdf, of the letter, so if I wanted to exaggerate and embellish and circulate a doctored version I easily could, but of course there’s no need). Dowden writes:

‘Rather than erasing these objects, we should seek to contextualise or reinterpret them in a way that enables the public to learn about them in their entirety, however challenging this may be. Our aim should be to use them to educate people about all aspects of Britain’s complex past, both good and bad.’

Learning from statues good, learning from TV bad.

He goes on:

‘Further, as publicly funded bodies, you should not be taking actions motivated by activism or politics. The significant support that you receive from the taxpayer is an acknowledgement of the important cultural role you play for the entire country. It is imperative that you continue to act impartially, in line with your publicly funded status, and not in a way that brings this into question.’

What Dowden is insisting is that, contrary to popular belief, museums are in fact neutral, have always been neutral, and should remain neutral or risk losing their taxpayer funding. It is a refusal to admit that any small part of the national myth portrayed in our museums for the past 150 years could be a fiction. The stories presented in museums have been written by a person, or a team, at a point in time. They can be just as much of a distortion, a fiction, just as much the product of a distinct point of view, as a script for an episode of The Crown.

What I think would be more helpful than the statues good, TV bad posture would be to encourage visitors and viewers alike to think critically about the history that is presented to them. To never assume impartiality or neutrality but to assess what is being presented and the context in which it was created. This skill, this approach to history, is something that people could learn from museums, if museums are given the freedom to re-examine and represent their collections, and not dictated to by government.

Thread on the Royal Museum for Central Africa

I expected to see some #MuseumsUnlocked content today about the Royal Museum for Central Africa. I have hesitated to post anything myself from my trip with @mus_ethno_group in Feb – I thought I might write a blog but I’ve found it hard to convey my thoughts.

This is the infamous display/not display which visitors (might) see at the beginning of their visit, off to one side of a gallery. It is supposed to look like storage but the effect is confusing #MuseumsUnlocked

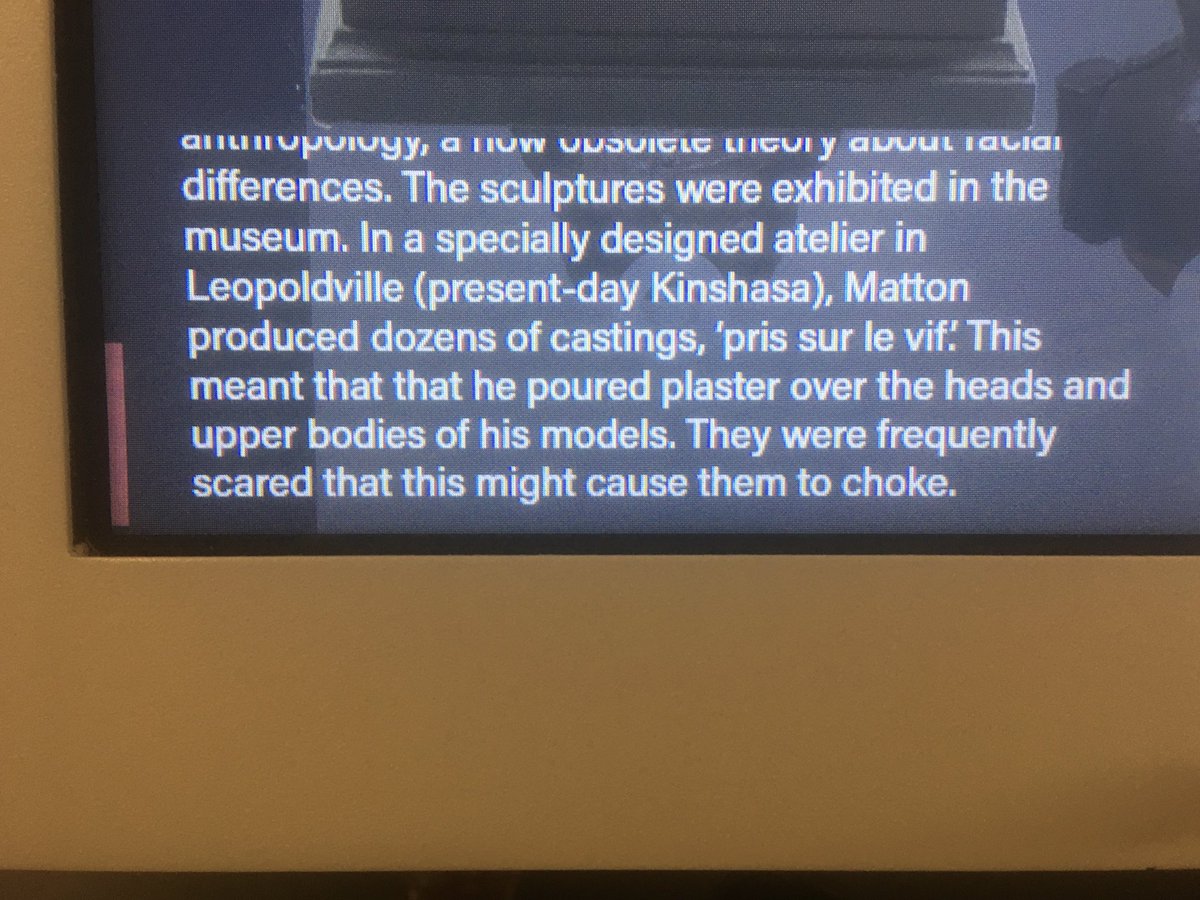

A screen next to the statues gives some more context – but, for example, this upsetting information about one of the busts on display/not display feels buried and easily missed. #MuseumsUnlocked

I had recently seen a more upfront exhibition about ethnographic plaster casts which I shared in another #MuseumsUnlocked

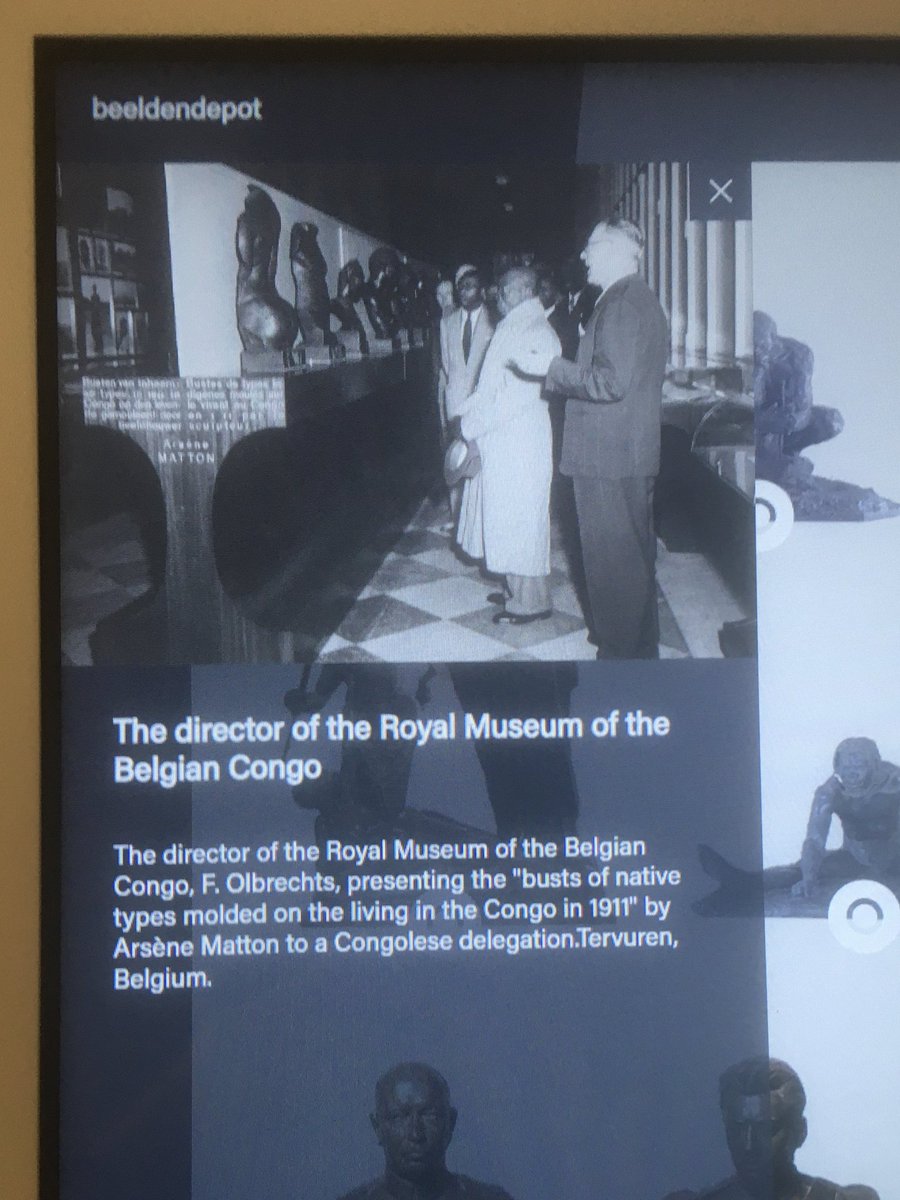

These same busts being presented by the museum director to a Congolese delegation to the museum 👀

My overarching feeling during the visit was that decolonising such a museum is an impossible task, and it made me question if any such museum should exist. I couldn’t understand why so much of the museum and research institute’s work was still, essentially, studying the Congo.

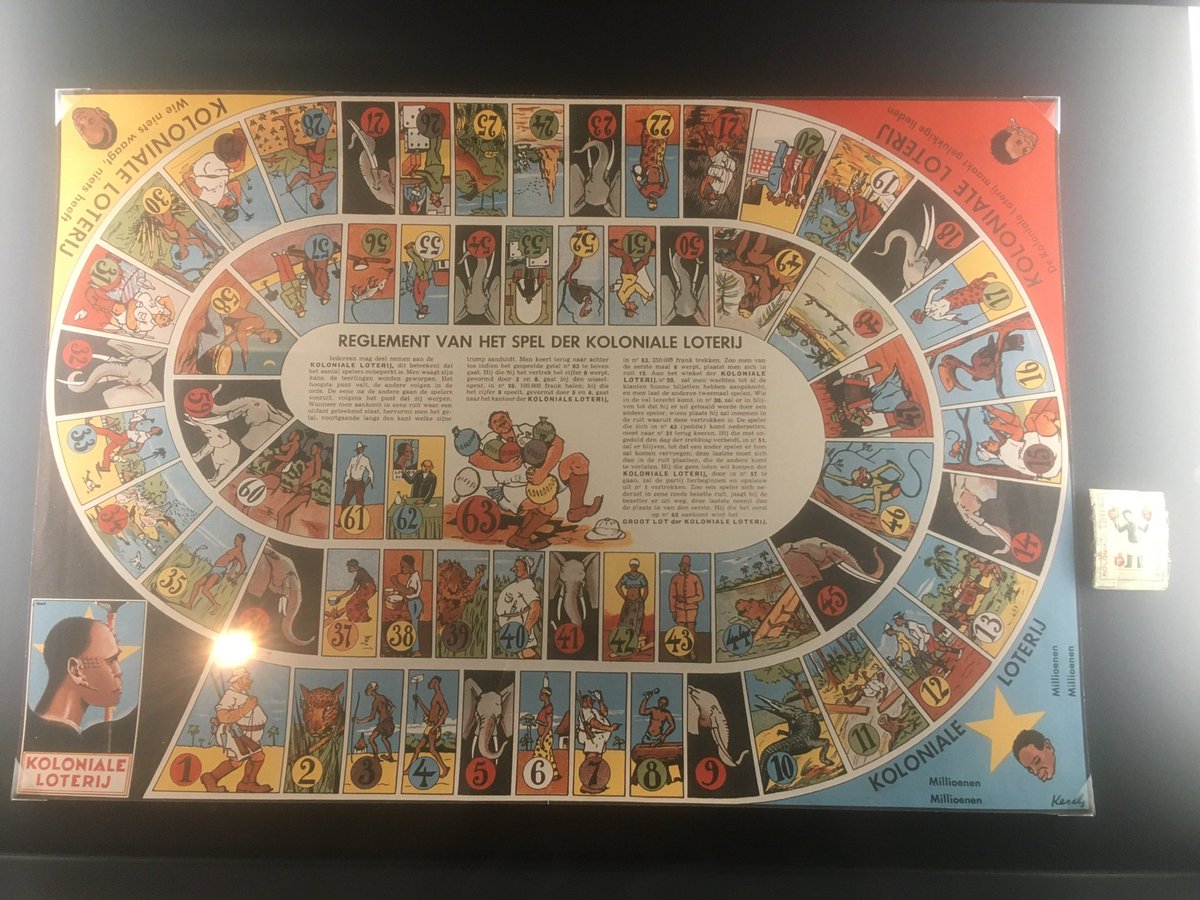

I respect the staff I met there who are attempting that task, and their commitment to responding to (inevitable) criticism. I wish I had got more of a sense of how the colony impacted Belgium, and not just the other way round. One hint was this Colonial Lottery board game.

Another was a Belgian man who we met on the tram to Tervuren, who chatted about buildings we passed. He’d been to the museum, but not since they’d reopened, he wasn’t interested in going back. As he got off he made sure to let us know that he’d lived in the Congo for many years.

Originally tweeted by Kathleen Lawther (@kathleenlawther) on May 21, 2020.