‘What a difficult thing a gift is for a woman! She’ll punish herself for receiving it.’ Zadie Smith

Earlier this month I flew to Belfast to spend two days wearing a tabard in a mock-up supermarket, in the middle of the Museums Association conference. As part of Museum as Muck’s Supermuckers intervention, I talked to hundreds of people. I asked them what their parents did for a living when they were growing up, and what they themselves do now. We talked about what that said about social mobility and whether they thought that mattered. I think it matters. There were times I had to go into a dark meeting room and hide because I needed 10 minutes not speaking to another person. There were other times I hunted down museum directors, heads of funding bodies and anyone I recognised with influence, interrupted their cosy chats and brazenly invited them into our supermarket to talk about class.

Many people openly shared their own experiences with us, good and bad. Of all of these, the sentiment that most struck me was something said among the Supermuckers crew over a bottle of wine while going over our notes the night before the conference.

It is a thought I have often had but found difficult to share. It can be summed up as ‘What is it about me that made me able to achieve?’ With no professional role models, with no one in my household working, with little external encouragement.

While researching our intervention I read a statistic about the ‘minuscule number of children on free school meals [who] pass the 11-plus.’ Minuscule. But I am in that number. I am an exception to this rule. Am I, therefore, exceptional? Why does this make me so uncomfortable? Why was my friend, a brilliant museum educator, a manager in a national museum, founder of a dynamic and fast-growing group which has brought together hundreds of working class people in the museum sector, wondering what made her able to do it all?

You could see the success of the members of our network as evidence of meritocracy in action. Perhaps this makes me uncomfortable because I believe meritocracy is a scam. I don’t want to be an example of how grammar schools can aid social mobility for a minuscule number of individuals because that’s not good enough.

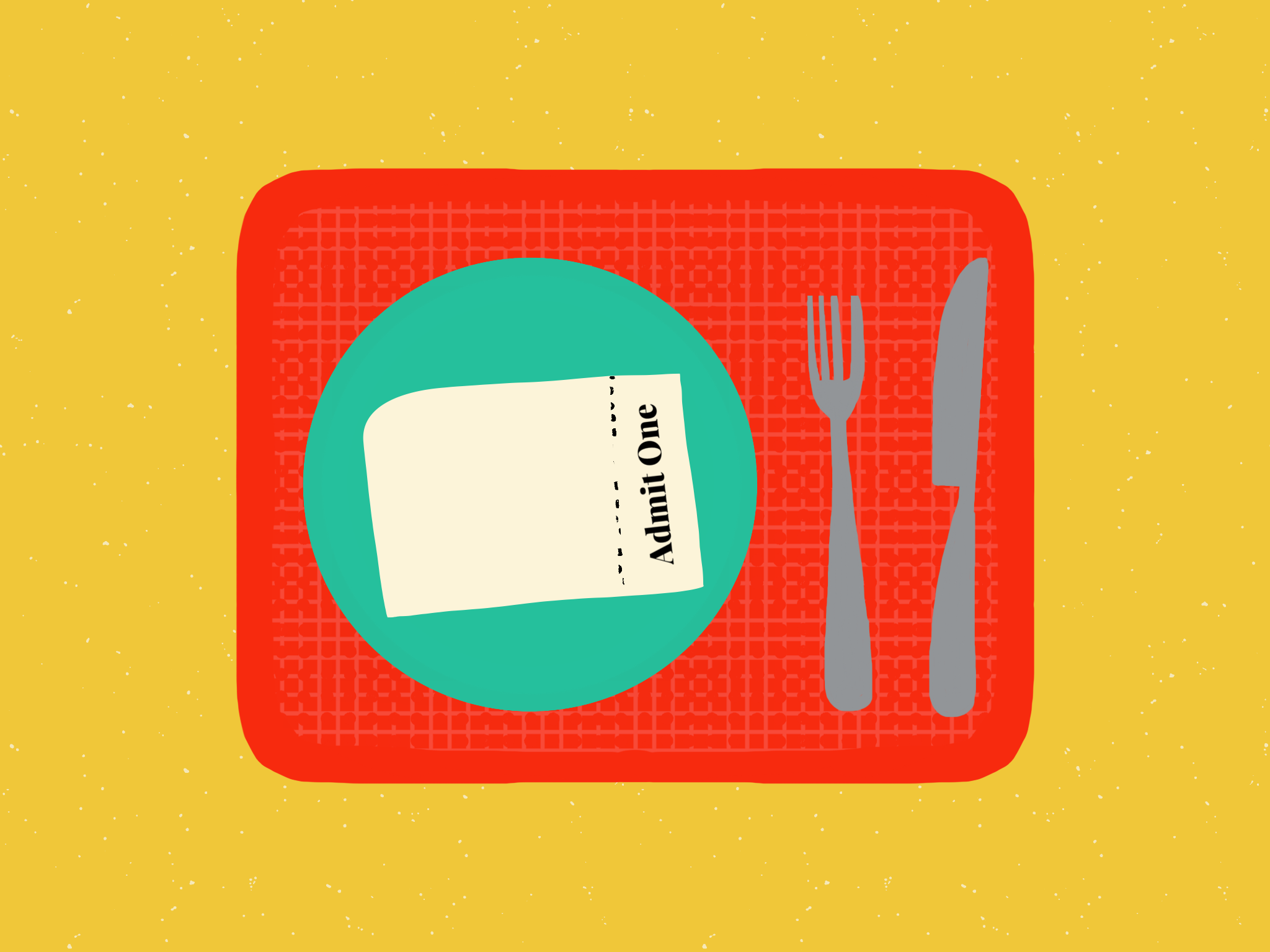

Alongside the statistics which lined the shelves of our supermarket, we included personal experiences anonymously shared by members of Museum as Muck. One of the most affecting of these accompanied a plastic tray symbolising free school meals:

‘At Primary School once I asked my Mum why I never had to bring money in little envelopes to school like the rest of the class. She told me she already paid the secretary. She was lying. She was embarrassed.’

Among the group we discussed this experience, which many of us understood all too well. The two of us who grew up in Kent and passed the eleven plus shared another experience: We both had free school meals at Primary School and still qualified when we made it to Grammar School, but our mothers didn’t want us to have them. They didn’t want us to stand out, and even though they couldn’t really afford it, they made it work so we wouldn’t have to. In each of these experiences our mothers sought to protect us, but they also taught us an important lesson – that being poor, that receiving benefits from the state, was something to be embarrassed about. We know all too well that we are statistical anomalies because we were taught from an early age to be ashamed of where we come from. We were taught to hide it.

We are uncomfortable with our success because we know it’s not expected. We feel the need to qualify it, to justify it, because we were never taught to expect it. I found myself talking to a few people at the conference about my childhood. I grew up in a single parent household where no one worked. I used to feel the need to justify my mother’s decision not to work. More recently I have felt the need to distance myself from it. Her decision, not mine. I was asking everyone who passed our stall to write down the occupation of the breadwinner in their household at 14. How many of those from affluent, comfortably middle class or ‘hard working’ class backgrounds felt the need to justify their relation to their parents occupation, or lack there of? How many had even thought about it until put on the spot by our intervention?

Coming from a background which you have been taught to be ashamed of requires you to jump through these mental hoops, in addition to the economic hurdles. I suspect that those who have been taught to expect to do well, who have seen their immediate families demonstrate how to succeed, do not spend time wondering what it is about them that allows them to achieve. I imagine they are able to enjoy their achievements safe in the knowledge that success is exactly what they deserve. Time and again during Supermuckers we directed visitors to the Panic! report, a ground-breaking piece of research on class and the creative industries. The findings of the report confirm what the muckers’ conversations suggested: that while we are anxiously wondering what it is that makes us exceptional and feeling like imposters, those with the most privilege are secure in the belief that they’ve earned it:

‘…there is one group that stands out–the highly paid. These respondents, who are in the most influential positions in the creative industries, believe most strongly in meritocracy. They are also most sceptical of the impact of social factors, such as gender, class or ethnicity, on explanations for success in the sector.’