I have written in previous posts about an emerging trend for museums to put on self-questioning displays which examine what museums and collections mean in society. I was excited by the prospect of the V&A’s All of This Belongs to You, which ‘examines the role of public institutions in contemporary life and what it means to be responsible for a national collection.’ The exhibition does this through a series of installations and interventions throughout the museum. While this was an interesting way to see more of the museum, I can’t help wishing that it was presented as more of a traditional exhibition, which might have made it more visible and accessible. The concept of the show is to engage visitors with the collection and museum as belonging to the nation, at a time when museums are under threat. I wish some museum would make this point more bluntly and loudly for all to hear.

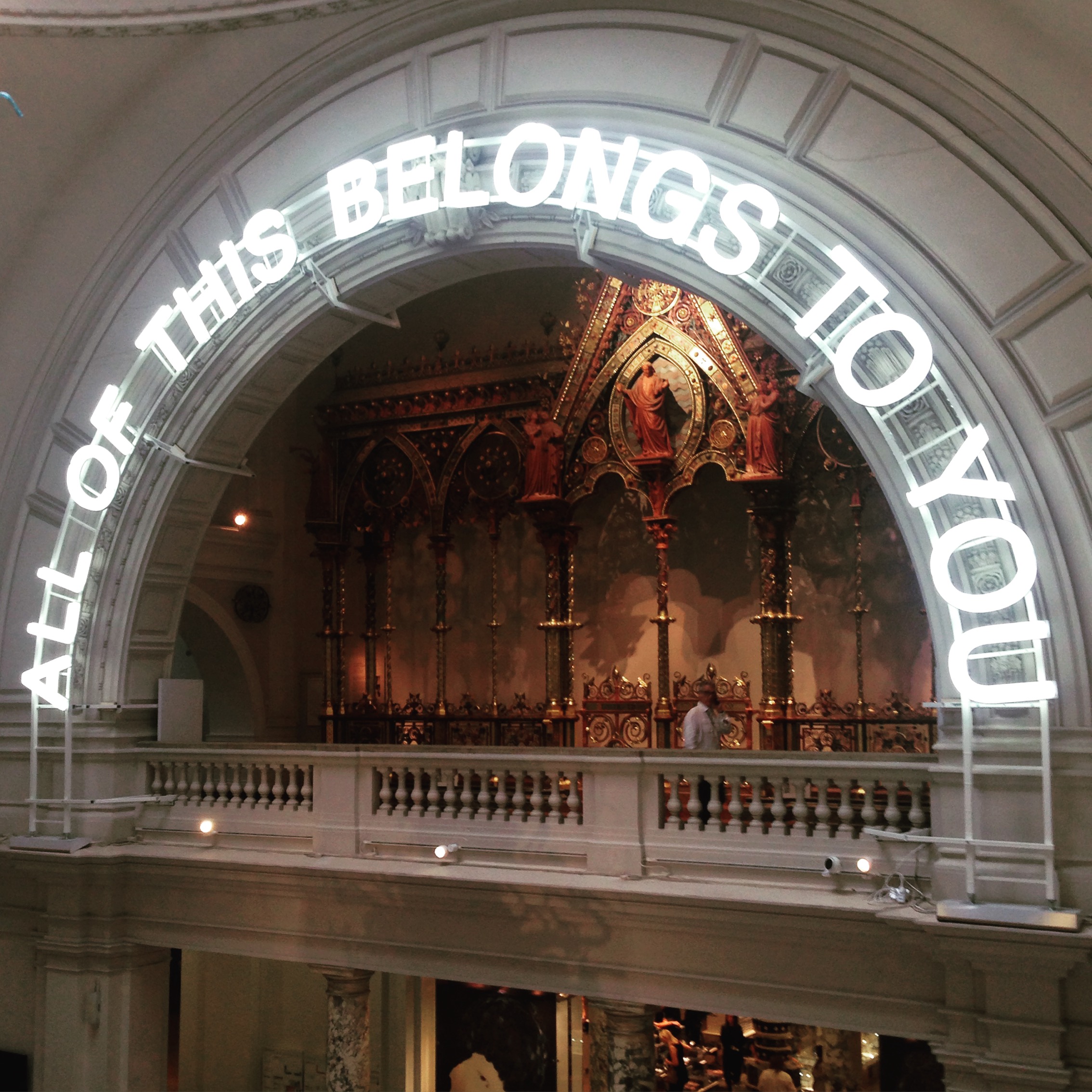

The first piece which many visitors will see does make the point loudly, in neon lights about the information desks, ‘all of this belongs to you’. It is dazzling and welcoming, and begging to be snapped and shared. Isn’t that what museum exhibits in a world of hashtags and selfies aspire to be?

On the day I visited there was a sound performance in the medieval and renaissance gallery. Despite being there to see All of this Belongs to You, following the exhibition trail and looking around the gallery for all the relevant new displays and panels, it took me a long time to find the small sign at the entrance which explained the performance. I was confused, and others more so, but the performance certainly had the desired effect of subverting the usually quiet and reverential atmosphere of the museum.

- Sound Out performance in the Medieval and Renaissance gallery

- muf architecture/art installation focusing on the idea of public space, involves an active use of the gallery.

The exhibition consists of four site-specific installations, two displays, and a trail of Civic Objects throughout the museum, which frustratingly required a different guide to be picked up from the information desk. I didn’t realise this until it was too late and I had already trekked up to Level 4 to see the Ways to be Public display. One of the successful side effects of following the trail was that it took me into galleries I had never visited before. As with all large museums, you can never see everything, and a visit to the V&A for me usually involves a temporary exhibition and picking one or two favourite areas to visit or re-visit. I had never been to the architecture gallery! Nor would I have made the effort to wind my way to the tapestry room where the Five Eyes piece is displayed. These discoveries, along with the rapid response collecting area, made the visit especially enjoyable for me.

Some of the installations were visually arresting – notably Jorge Otero-Pailos’ great illuminated column The Ethics of Dust highlighting the vestiges of Victorian chimney hidden inside the museum’s Trajan’s Column cast. James Bridle’s Five Eyes also looked slick, showcasing museum objects, linked together by data, visually represented by displaying the objects’ registry files and associated documentation. I liked the fact that putting the documentation in the case made visible the work that goes on behind the scenes but I do work in collections management, and to others this may have just looked like a pile of boring folders. The stacks of folders also provided a pleasingly analogue presence in an installation concerned with data – a reminder that although digital advances make big data possible, museums have always dealt in information.

Bridle’s work uses an algorithm to select and connect objects based on metadata from the V&A’s digital records. This means that to the visitor the connections are obscure and pretty incomprehensible; we are used to objects being presented together within a coherent theme. This is a good example of something I touched on in my round-up of the BM’s data conference – algorithms can make connections and ‘curate’ content, but that doesn’t necessarily make for a good viewing or visiting experience.

While the meaning of Bridle’s work is not immediately apparent (the accompanying website makes it clearer and allows you to play with the algorithm to create new networks of objects) the gallery text repeated on each of the cases in Five Eyes does make a crucial point about museums and the organisation of knowledge:

‘The way in which we order museums tells us as much about ourselves as the things they contain. Museums, software programmes and intelligence agencies are all models of the world. Who designs them and operates them, whose politics they embody, and whose stories they tell, shape the world we all inhabit. If these institutions really belong to us, they must be more than experienced, they must be understood.’ James Bridle

This idea that museums as institutions should be unpicked and understood is one that has long been the subject of museum studies discussions, but it is now increasingly cropping up in the public face of museums in exhibitions like All of This Belongs to You. Museums need to do this kind of self-examination in order to better equip themselves for the future, but it cannot be an introspective exercise. I think it is important that museums encourage the public to consider what museums do in society, to understand it, and to question it. We need the public to engage with the role of the museum in order to champion that role as well as to critique it and push it forward. Campaigns in other media such as social media may draw attention to issues facing museums, but museums shouldn’t lose sight of the best tool that they have to engage people with these ideas, through exhibitions and displays.