I recently shared an article on Twitter, ‘The Boleyns and the Bechdel Test’ about two costumed interpreters’ efforts to create heritage interpretation at Historic Royal Palaces which would pass the Bechdel Test.

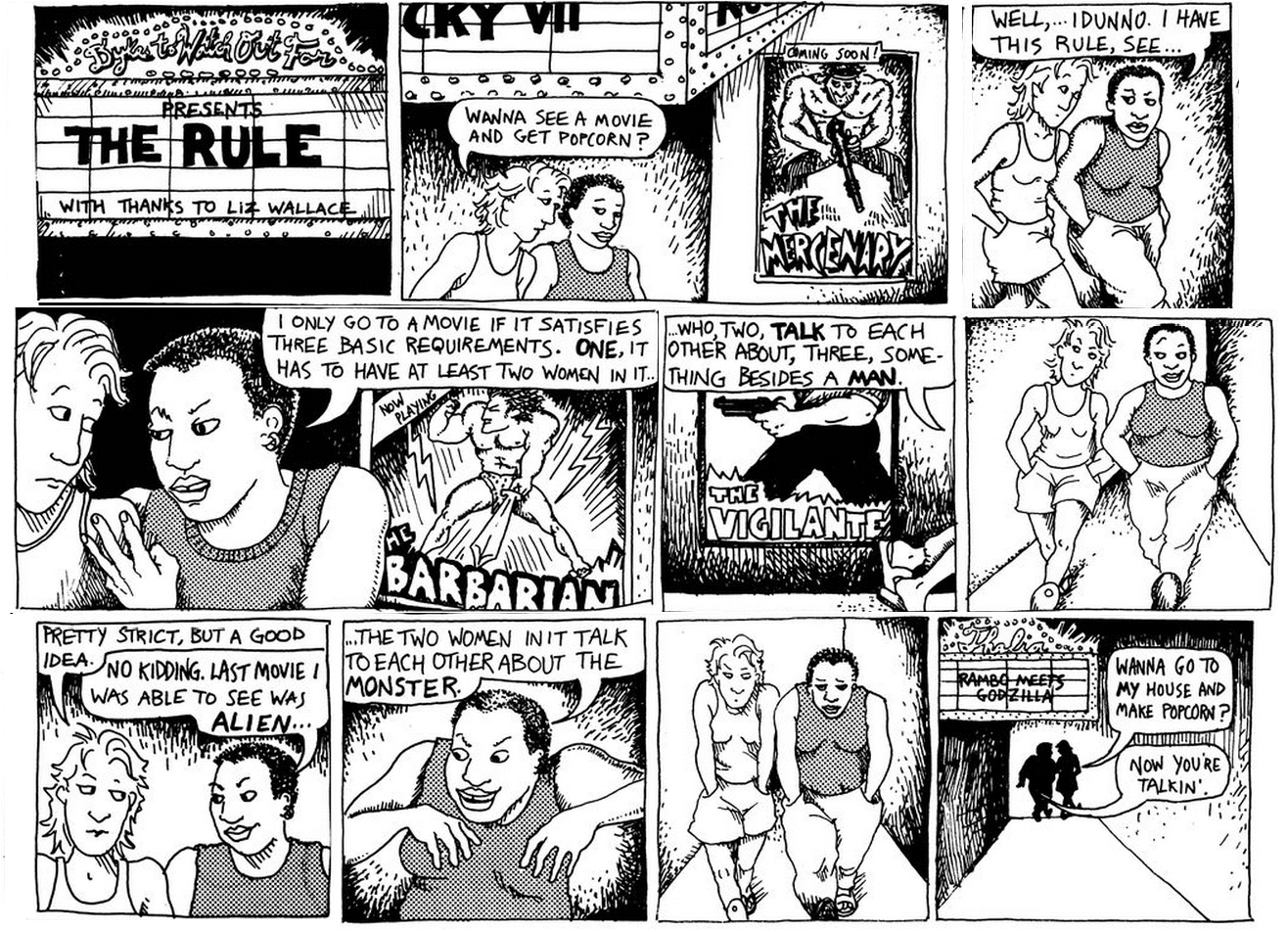

If anyone is unfamiliar with the Bechdel Test, it is a way to judge the representation of women in films, and originates from this cartoon strip by Alison Bechdel:

In order to pass the test a film must have:

1. Two female characters…

2. who talk to each other…

3. about something other than a man.

In the example described in History Riot’s article, the two female characters are Anne Boleyn and her sister-in-law Jane Boleyn. By playing their scenes at Hampton Court Palace according to the three rules, interpreters were able to show visitors fuller, more realised versions of Tudor womanhood, discussing the two women’s political and religious standpoints. The article touches on the importance, especially for young visitors, of seeing women portrayed as active and engaged with historical issues, instead of being sidelined as the wife, mistress or muse of a male historical figure. I also thought it was interesting that these women have often been portrayed as rivals, which is a trope we still see in the media today of famous and influential women being pitted against each other.

This fantastic example got me thinking about how the Bechdel Test could be applied in other heritage and museum settings. While the art of costumed heritage interpretation is comparable to film in its use of characters and dialogue which means it lends itself well to the scrutiny of the test, museums and exhibitions are a slightly different story. I wanted to consider how these rules could relate to museum formats. Exhibitions are often seen as narrative, and storytelling is an increasingly important element in exhibition design. But an exhibition narrative is different to a film narrative, which the Bechdel test is designed for.

The individuals named in a museum exhibition do not speak as such, although they may be quoted in the interpretive text. They can not interact with each other as they would on film, but there could be two women mentioned in the same section of an exhibition whose narratives within the display interact. The ‘about something other than a man’ element is relevant to museums. If the woman only appears as a visual in a portrait painted by a man, or is featured she is the wife or mistress of a man whom the interpretation is focusing on, that’s a big fail for the museum Bechdel test.

I’m reminded of the National Maritime Museum’s recent Pepys exhibition, which featured a section of portraits of Pepys’ female contemporaries, including Nell Gwyn, Barbara Villiers and Moll Davis. The section of the exhibition was entitled ‘Court and Pleasure’, which immediately set alarm bells ringing for me. Here was the section of the exhibition which has the most representation of women, and they were explicitly being linked to the theme of pleasure – you can bet it wasn’t the women’s pleasure that anyone had in mind. This exhibition also featured on it’s posters and branding an illustration of Pepys flanked by a naked woman whose hair coyly covered her nipple. This was irksome not simply because of the implied nudity (which was after all only a drawing) but because it was using the women on the poster, which also featured Charles I and his executioner, simply as set dressing to the more important and recognisable men, much like one dimensional female characters in the movies who only serve as accessories to the male characters who drive the plot.